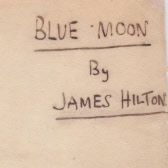

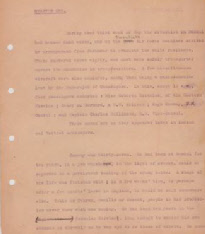

HILTON, JAMES (1900-1954). FINAL ANNOTATED DRAFT TYPESCRIPT OF LOST HORIZON, [Woodford Green, Essex, April 1933], 257pp., 4to (10 x 8 inches), 206 with authorial manuscript revisions, corrections, deletions, and insertions in black ink, 61 of which include textual changes present in the work’s first edition, the first leaf with the author’s initial working title, “Blue Moon,” in handwritten block letters and signed [“James Hilton”], followed by a typed but unnumbered half-title and prologue title, all other leaves hand-numbered at the top right corner as follows: 1-128, 128A, 128B, 129-206, 206A, 207-209, 209A, 210-211, 211A, 211B, 211C, 212-236, [a single page designated “237-242”], 243, 243A. [Unnumbered epilogue title page], 244-253. All leaves have four uniform holes in the left margin for insertion in a binder and are age-toned with occasional minor chipping; many have additional blue-pencil and ordinary-pencil corrections in two other distinct, certainly proof-corrector, hands (see below). The final three-and-one-half paragraphs of the epilogue (918 words) are not included with this typescript; this missing portion constitutes four typewritten pages at Hilton’s rate of roughly 215-230 words per typed page and may represent a final set of changes to the novel’s coda delivered later under separate cover. Otherwise the typescript is entirely complete and corresponds to the printed text of the first edition, with each leaf now placed in an archival Mylar sleeve and the entire manuscript housed in a new custom quarter-morocco slipcase. Provenance: “The Papers of James Hilton” Christie’s Los Angeles 18th November 1999 (lot 83).

One of the most celebrated and best-loved novels of the 20th century, LOST HORIZON in 1933 introduced “Shangri-La” to the English language and remains the 20th century’s most renowned fictional vision of modern utopia. LOST HORIZON was typed by the author himself at his parents’ modest semi-detached home at Woodford Green, Essex in April of 1933 after an intensive six weeks of composition. It was submitted to and immediately accepted by the London publishing house Macmillan sometime before May 9th, 1933. Also in early May 1933, a successful arrangement was made by Macmillan for LOST HORIZON to be published simultaneously in the United States on September 26th, 1933 in association with Hilton’s already established New York publisher William Morrow. The corrected ribbon typescript of the final draft of the novel was sent to Macmillan and this, the corrected carbon copy, was sent to Morrow.

There are some minor but fitfully significant textual differences between the first English Edition and the first U.S. edition and these small differences exist entirely due to William Morrow’s last- minute efforts to provide the novel with “Americanization” for its readership. Upon receipt of the present typescript in New York, Morrow put its blue pencil to work. The alterations made by this corrector can be found most prominently in the improvement of those speeches made by the one American character in LOST HORIZON: Barnard, the disgraced post-1929 Wall Street Crash stock swindler on the run. In addition, Morrow’s corrector did a little translating for American readership (e.g. “petrol” became “gasoline,” “gramophone” became “phonograph”). Further, a dose of editorial polish was added to Barnard’s argot, as Hilton’s ear for American slang wasn’t completely true. It also appears, surprising as it might seem that Hilton did not review the American galleys as every single one of Morrow’s blue-penciled changes, even those of slightly dubious value, seem to have made it into the first American edition.

William Morrow’s revisions of the text had consequences for posterity. In 1939 the American text became the standard due to LOST HORIZON’s publication that year as the historic first-ever American mass market paperback (Pocket Books #1) which was reprinted 105 times by the 1960s and translated into thirty-four other languages. By 1969, Pocket Books alone had sold two million copies around the world.

The adaptation of the 1933 novel into the 1937 film further enhanced LOST HORIZON’s worldwide fame and the film has long been considered a cinematic classic. It received seven Oscar nominations (including Best Picture) and became the sixth highest grossing film of the 1930s. Its reputation, like the novel’s, continues to grow after almost 75 years.

The making of the film can be credited to the unrelenting and inspired efforts of three-time Oscar winning director Frank Capra (“It’s a Wonderful Life” “Mr. Smith Goes To Washington,” “You Can’t Take It With You) who fell in love with LOST HORIZON after idly purchasing the novel for casual reading on a train. He noted in his autobiography that: “I read it; not only read it, but dreamed about it all night.” The film adaptation starred Ronald Colman in one of the many roles he seemed born to play and its much-lauded screenplay was written by Capra’s favorite Oscar-winning scribe, Robert Riskin who, in consultation with Hilton himself, wrote a script which was faithful to the dreamlike quality of the book. Riskin’s sensitive understanding of the novel can be heard in lines of dialogue such as one murmured by Sam Jaffe as the two-hundred-year old High Lama: “There are moments in every man’s life when he glimpses the eternal…”

The fact that Frank Capra actually purchased the first heavily corrected draft of the manuscript itself directly from James Hilton (along with the film rights) in 1935 is not quite as odd as it might seem for two well-documented reasons. Capra was already in the process of building a remarkable literary library with the help of legendary rare book dealer Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach. And Capra shamelessly used his purchase of the manuscript as part of his publicity campaign to spur interest in the film. For example, Time Magazine’s review of the film’s premiere in its March 8th, 1937 issue stated that “Director Capra went to work with typical Hollywood opulence. He bought the original manuscript.”

In actual fact, Capra bought two manuscripts of LOST HORIZON, first draft and final draft, both of which appeared together in Parke-Bernet’s April 1949 sale of Frank Capra’s library. The “first draft typescript,” as described in Parke-Bernet’s sale catalogue, consisted of 259 leaves. It had been typed rapidly without editing or pause as was consistent with Hilton’s working methods throughout the entire length of his prolific career. It was also typed on the versos of the original manuscript of Hilton’s earlier novel TERRY which had been published in 1927, an odd frugality but not altogether surprising given that Hilton was still living and writing at his parents’ house during the time of LOST HORIZON’s composition. Despite eight published novels, by 1933 he had achieved neither literary nor financial success. This “first draft typescript” was then revised via erasure, over-typing, and interlinear holograph additions. All these working methods are depicted in the Capra catalogue, in the plate reproduced opposite Lot 207’s printed, full-page, description. Along with the first draft in the Capra sale, there was a final draft typescript (the corrected ribbon copy) of LOST HORIZON. Here follows an excerpted section from Parke-Bernet’s complete description in 1949:

“Included with the original is the finished copy, also containing a few corrections in the author’s hand, on 257 quarto leaves. This was the script used by the printers, containing the galley marks as the book was set up. In addition a covering letter from the author is included, verifying that the script was typed and corrected by him, and that no duplicates or counterparts exist except the finished copy. The whole of Mr. Hilton’s famous book through the inception and development to the finished story [sic]. With the exception of interlinear corrections (which are in holograph) the whole of Mr. Hilton’s work is done on a typewriter, no book or article having ever been written in manuscript...”

What Hilton may have forgotten to tell Frank Capra in 1935 was that there was a third typescript extant, the corrected carbon copy final draft in the possession of William Morrow.

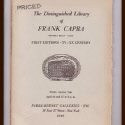

Parke-Bernet’s “official priced catalogue” of the Capra sale in 1949 shows that this lot 207, containing two LOST HORIZON typescripts, was sold for $450. Whether from that sale or perhaps due to a later transaction, the two typescripts from the Capra sale ended up in the Pennsylvania State University manuscript archives. This most likely was unknown both to the Hilton heirs as well as Christie’s Auction House when, on the 18th of November, 1999, “The Papers Of James Hilton…acquired from Hilton’s heirs” appeared for auction at Christie’s Los Angeles. Various letters, photographs, even Hilton’s ink stand, were sold along with the manuscripts (first and final corrected typescripts) of ten of Hilton’s other novels, but both Capra’s typescripts and the “covering letter” for LOST HORIZON described in the 1949 Capra sale catalogue were nowhere to be found. Both Christie’s and the Hilton heirs asserted in the 1999 catalogue description that theirs was the “annotated original manuscript of Hilton’s most celebrated novel…” and that “…although Hilton had donated some of his manuscripts to the Library of Congress, he kept this, his most important work. It was discovered among his personal papers…” In actual fact, their copy was the corrected carbon final draft manuscript which was returned to the Hilton family by William Morrow at some unknown time.

As Frank Capra’s copies of the first and final Macmillan corrected drafts survive in the vault at Pennsylvania State University, then ours is the only available manuscript of LOST HORIZON and, as such, is one of the few great literary manuscript works of the twentieth century still remaining in private hands.

References: Hammond, John R. The Lost Horizon Companion: a guide to the James Hilton Novel and its Characters, Critical Reception, Film Adaptations and Place in Popular Culture (London and Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, [2008]. Capra, Frank. The Name Above The Title (New York: Macmillan, [1971]. Six Screenplays by Robert Riskin edited and introduced by Patrick Gilligan (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, [1997]. HOME

Featured Manuscript - Lost Horizon